Photo by Lubo Minar on Unsplash

Six African American Lawyers to Celebrate during Black History Month

Published February 15, 2022

In recognition of Black History Month, we want to highlight some of the most successful, influential, and well-known African American lawyers throughout United States history. Their impact should not only be celebrated for their work within their legal field, but for their impact as role models to many young African Americans during their time and in the years that followed.

Charles Hamilton Houston

Photo by Addison N. Scurlock, courtesy of the Archives Center at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

Known for being the first general counsel of the NAACP, Charles Hamilton Houston was a champion of various civil rights cases and earned the moniker “The Man Who Killed Jim Crow”.

A son of an attorney and a former teacher, Houston was no stranger to education. He attended Amherst College, where he was the only African American student in his class, and graduated with his LL.B. in 1922.

Growing up in between two world wars, Houston experienced segregation both at home, and on the front. While serving in the U.S. Army as First Lieutenant during WWI he pledged his intent to study law:

"The hate and scorn showered on us Negro officers by our fellow Americans convinced me that there was no sense in my dying for a world ruled by them. I made up my mind that if I got through this war I would study law and use my time fighting for men who could not strike back." – Charles Hamilton Houston

Submit this form to receive an application fee waiver.

Sure enough, in 1924 Houston would complete his Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D.) at Harvard School of Law. He would also be the first Black student to be elected to the editorial board of the Harvard Law Review. Following this, he would complete a year of study at the University of Madrid before passing the District of Columbia bar exam and joining his father's law practice in Washington, D.C.

From there, Houston would serve as an administrator, dean, and professor at the newly established Howard University. Through Houston's leadership, the school received accreditation through the Association of American Law Schools, and would later become a "Black Ivy League" School, training future legal scholars for generations.

In 1935, Houston would be offered the position of legal counsel by the NAACP. There, he would work toward his goal of overturning the Plessy v. Ferguson case of 1896, which was known to be the structural holding of the "separate but equal" doctrine. Houston would go on to win various cases, and would most notably assist Lloyd Gaines in the case Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada.

Lloyd Gaines, a Missouri resident, sought admission into the University of Missouri Law School, an all-white university, and the state's only public law school. At the time, no "black" law school was available in Missouri, and Houston argued that though the state had offered to pay Gaines's tuition to attend a law school out of state, Missouri had a duty to provide him a qualified "equal" legal education within the state. His argument was founded in that there was no "separate but equal" facility within the state, and the Supreme Court agreed. Gaines was formally admitted to the University of Missouri.

Through this strategy, Houston intended to show that keeping "equal" facilities were too expensive for states to hold up. The idea worked and began to pave the way for desegregation through cases such as Lloyd's. Though Houston's life would be extinguished early in 1950 from a heart attack, he would live on through his famous arguments and the continuous teachings given to young scholars such as Thurgood Marshall by Howard University.

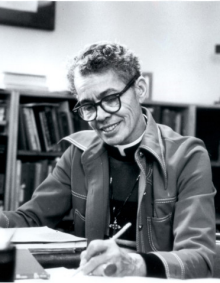

Dr. Pauli Murray

Perhaps you have not heard much of Dr. Murray, but chances are they influenced many of the cases, figures, and organizations you hear about every day.

The fourth of six children to Agnes Fitzgerald and William Murray, Pauline’s mother passed away only a few years after her birth. Shortly after, her father would suffer from depression and typhoid fever, being admitted to Crownsville State Hospital where he would later be murdered by a white guard. Pauline was only 13. Orphaned at a young age, Pauline would live with her aunt and grandparents in Durham, North Carolina.

After a strained early life, Murray would prove to be increasingly intelligent, graduating from her high school in 1926 with a certificate of distinction and gaining entrance into Hunter College in New York City. Murray would work various jobs to pay their way through college, graduating with a degree in English Literature in 1933.

Shortly after, s/he would change their birth name to “Pauli”, and would pursue gender-affirming medical treatments, including hormone therapy, which s/he was denied. At this same time, Murray worked for the Works Projects Administration as a teacher at the New York City Remedial Reading Project. S/he would write and publish an exorbitant number of poems and articles in various magazines including Common Sense and The Crisis, a publication by the NAACP.

As Murray delved deeper into civil rights, s/he soon would be arrested and imprisoned for refusing to sit at the back of a bus in Richmond, Virginia in 1940. In 1941 however, Murray would enroll in Howard University with the intention of becoming a civil rights lawyer.

Through their work with William Howard Hastie and Leon Ransom, Murray was able to produce a senior thesis at Howard University, titled “Should the Civil Rights Cases and Plessy be Overruled?”. S/he enjoyed discussing their thoughts on the cases, and their immorality, with their classmates, but would be met with mocking laughter. Through this experience Murray coined the term “Jane Crow” which s/he would use through various writings to explain the forms of sexist derision s/he encountered during their time at Howard University. Ten years later, Thurgood Marshall, Spottswood Robinson, among others would review Murray’s senior paper and utilize its arguments to strategize their impending case Brown v Board of Education. No credit was given for almost ten years, when Murray would encounter Robinson at Howard Law School.

It was not long before Murray would graduate at the top of their class, earning the Rosenwald Fellowship that would lead Howard graduates to Harvard University. Murray however, was rejected from Harvard Law on the basis of s/he’s gender. Despite this, Murray would attend the University of California’s Boalt School of Law where they would receive a Master of Laws Degree. During this time, Murray struggled with their sense of gender identity, and their sexual attraction to women, but no support was given by doctors, nor was the term transgender available until the 1950s.

By this time, Murray was an up-and-coming civil rights attorney. S/he would go on to support the movement through their continuous work as a lawyer while also authoring various books. Murray would also soon be suppressed by McCarthyism, losing a position with the U.S. State Department, but would also soon be offered a position within the new law firm Paul, Weiss, Rifkin, Wharton, and Garrison.

In Murray’s later life they would go on to be appointed to the Committee on Civil and Political Rights as a part of John F. Kennedy’s Presidential Commission on the Status of Women. In addition, they would found the National Organization for Women alongside Betty Friedman, and would later serve as a faculty member of Brandeis University from 1968 to 1973. Following the loss of their longtime partner, Irene Barlow, Murray would leave their tenured position to become a candidate for ordination at General Theological Seminary. In 1977, Pauli Murray would become the first African-American person perceived as a woman in the U.S. to become a Episcopal priest.

Murray would pass in 1985 after a lengthy battle with cancer. Their work would continue to inspire longer after their withdrawal from teaching, with various books releasing posthumously, and their works being republished through the ages. Ruth Bader Ginsburg would also credit Murray’s work as inspiring her brief in the Reed v. Reed case, which ruled that women could not be excluded as administrators of personal estates based on their gender. She would later name Murray co-author of the brief, stating: “We knew when we wrote that brief that we were standing on her shoulders”.

*Though today we have a greater understanding of language and terminology surrounding gender expression and LGBTQ+ communities, Pauli Murray’s society did not. As we are unaware how Pauli Murray would identify if s/he were alive today, we utilize s/he and the universal “they/them/theirs” to refer to them out of respect for their choosing of a gender-neutral name, and use of both he/him and she/her in their academic works, personal journals and writings.

Thurgood Marshall

Arguably one of the most prominent civil rights lawyers in United States History, Thurgood Marshall is best known for dismantling segregation in America and arguing for the historic 1954 case: Brown v. Board of Education.

Marshall grew up in Baltimore, Maryland, where he experienced racial discrimination from a young age. After being forced to go to an all-black grade school, Marshall's family worked hard for him to later attend a first-rate high school. In 1930 he would graduate from Lincoln University with a rich interest in civil rights, debating, and the law. Later, he would go on to apply to the University of Maryland Law School where he would be denied admission due to the color of his skin. After being denied, Marshall set out to attend Howard University, where he would earn his LLB and graduate as valedictorian of his class in 1933.

Following his denial of a postgraduate scholarship to Harvard, Marshall began his own practice in his hometown of Baltimore. There, he would take on cases regardless of a client's ability to pay. Later, he would volunteer for the NAACP and eventually become one of their attorneys. Marshall would go on to win his first case against the University of Maryland Law School, which argued that African-American's should be allowed admission to the school regardless of their skin color.

After many years of assisting and, in many ways, leading the NAACP in its legal movements, Marshall would take on various civil rights cases. In 1952 Marshall would have the opportunity to serve as Chief Attorney for the plaintiffs of Brown v. Board of Education, arguing that school segregation itself was a violation of individual rights under the 14th Amendment. The Supreme Court agreed and declared that racial segregation violated the 14th Amendment. After four years sitting as a federal judge on the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in New York City, Marshall would find himself as the next Solicitor General. No more than two years later, Thurgood Marshall would be the first African-American Associate Justice to be appointed to the Supreme Court.

As a part of our recognition of Black History Month the University at Buffalo School of Law recently hosted "Growing Up Marshall". This event provided reflections from Thurgood Marshall’s son, John W. Marshall, with commentary from our Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, alongside members of the Law School’s Black Law Student’s Association.

Barack Obama

Before Barack Obama was elected as the first African-American President in United States history he served as both a community organizer and civil rights attorney.

Having graduated from Columbia University with his B.A. in Political Science in 1983, Obama would begin his work as a community organizer as Director of the Developing Communities Project in Chicago. There he would help set up a job training program, a college preparatory tutoring program, and a tenants' rights organization.

However, it was not long before Obama felt an urgent call to law school. After denying a full scholarship to Northwestern University School of Law, Obama set out to join Harvard Law School in the fall of 1988. Through his time there he was selected as an editor for the Harvard Law Review, and a research assistant for Laurence Tribe.

During the summers Obama would work as an associate in various law firms, and in his second year of law school, he would be named the first African-American President of Harvard Law Review. The announcement gained national attention, and soon after graduating with his JD in 1991 Obama would be invited to the University of Chicago Law School. There, he would spend various years writing a book, which would later become a personal memoir. Dreams from My Father was published in mid-1995.

Following the publishing of his book, Barack would settle down with his wife, Michelle, in Chicago. He worked continuously to direct Illinois' "Project Vote", and taught constitutional law at the University of Chicago Law School for twelve years. During this time, he would also serve as an associate attorney, then counsel, and later, as a full-time lawyer for Davis, Miner, Barnhill & Garland.

Though Obama's time as a lawyer was a successful one, having each of his major cases resolved in favor of him and his clients, his heart lied in politics and community organization. After serving on the board of directors of more than six community and law-based organizations Obama would announce his candidacy for a seat in the Illinois State Senate in 1995. Over the years, Obama would be elected to the State Senate and U.S. Senate before being elected as the first, and currently only, African-American President in United States history. Though he is best known for his time as President, his many years in law, and in his community have not been forgotten in Chicago.

Image from Library of Congress

Jane Bolin

A native New Yorker herself, Jane Bolin was born in Poughkeepsie, New York in 1908. The youngest child of her parents, Bolin would work hard to excel in school, following the early death of her mother when she was only eight years old.

And excel she would. Bolin went on to live through and experience discrimination in Poughkeepsie, while diligently studying and preparing for college. As a child and teenager Bolin would consistently be denied service at businesses due to her race, and, during her senior year of college, would be denied enrollment at Vassar College on the basis of the college not accepting black students. Despite all of this, Bolin would graduate from high school early, and at the age of sixteen would enroll in Wellesley College in Massachusetts.

Shifting to a new life in a new state, Bolin would be one of two black freshmen on Wellesley’s campus. Although she was at the top of her class, Bolin’s career advisor at Wellesley would discourage her from applying to Yale Law School due to both Bolin’s race and gender. When it came time for graduation though, Bolin would be recognized as being in the top 20 of her class, receiving her Bachelors of Arts, and an acceptance letter from Yale Law School.

Not a stranger to being the minority, Bolin would diligently study at Yale as one of the youngest of her class. There, she was one of only three women, and the only black student attending Yale Law School at the time. Despite her unique situation, Bolin would graduate from Yale in 1931, becoming the first African-American woman to graduate from the law school. She would then go on to pass the New York State Bar Exam in 1932 and would return to practice with her father in Poughkeepsie for a time.

Not long after Bolin’s entrance into the legal field she would marry fellow attorney Ralph E. Mizelle and would relocate to New York City. There, she took on assistant corporate counsel work for the city, becoming the first African-American woman to hold the position. Several years later Bolin would be called to appear at the World’s Fair by then-mayor of New York City Fiorello La Guardia. Unbeknownst to Bolin however, upon her attendance of the fair, Mayor La Guardia would swear her into the New York City Domestic Relations Court. History would be made on that day, July 22nd, 1939, as Bolin became the very first African-American female Judge in the United States of America.

Bolin would continue to sit on the court for forty years, as the court was renamed, and her appointment was renewed three times. During her time as judge, she worked to ensure that probation officers were assigned without regard to race or religion, and publicly funded childcare agencies accepted children without regard to ethnic background. After many years serving, Bolin would turn seventy years old and would be required to retire from her seat on the court. This, however, did not stop her continued interest in the law and justice. Bolin would be a continuous activist for children’s rights and education; working as a legal advisor to the National Council of Negro Women and serving on the boards of the NAACP, the National Urban League, and the Child Welfare League.

Bolin would continue to volunteer her time in her later life, and would also assist in building a school for young African-American boys. As she grew older she would remain a role model for many youths in New York City, passing away only recently in 2007, at the age of 98.

Photo by James Duncan Davidson

Bryan Stevenson

Perhaps less known than others on this list, Bryan Stevenson is the author of Just Mercy , an unforgettable true story about the potential of mercy in America. The book tells the story of Stevenson's life as a lawyer, Walter McMillian, an Alabama resident, and the Equal Justice Initiative.

Stevenson grew up in a rural community in Delaware in 1959. In his early life, he began to learn about the divisions that stand between humans and would reflect on these divisions when he entered Harvard Law School. Though unsure of what field of law he would choose, Stevenson found himself exposed to people desperately in need of legal assistance through his work with the Southern Prisoners Defense Committee. Following Stevenson's graduation from Harvard, he would work as a staff attorney for the Southern Center for Human Rights in Atlanta, and then as an executive director of the Alabama Capital Representation Resource Center. Here, Stevenson would represent capital defendants, and would take on the product of the civil rights movement: freedom in law, but not in the upholding of it. As Stevenson argued in courts he would be met with consistent difficulties when facing institutions and policymakers, many unwilling to uphold the law without court intervention.

In 1995 however, Stevenson would found and become executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). The nonprofit organization's goal has been to provide legal representation to indigent defendants and prisoners who have been denied fair and just treatment in the legal system. Under his leadership, the EJI has grown considerably, and has won many major legal challenges; eliminating excessive and unfair sentencing, exonerating innocent death row prisoners, confronting abuse of the incarcerated and mentally ill, and aiding children persecuted as adults.

Through his work, Stevenson has brought about various changes to both his local community and the greater United States legal community. He has won various awards and has initiated countless anti-poverty and anti-discrimination efforts. His memoir, Just Mercy, tells his unforgettable story as an attorney, was widely reviewed and praised, and has been adopted by many universities across the country as "college-level reading". In 2018 a Young Adult Adaptation was released and is now taught in many High School English classes. The memoir was similarly adapted into a feature-length film of the same name in 2019.

Though there is much more to say of Stevenson’s achievements, and his various efforts and experiences, you can find much of his story in his novels, Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption and Just Mercy (Adapted for Young Adults): A True Story of the Fight for Justice.

Happy Black History Month from the University at Buffalo School of Law! For more information on how the School of Law supports students of color, and promotes and advocates for inclusion, visit the Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion.