A new approach to the classroom

Faculty adjust and the learning continues

“We’re going to figure this out together.”

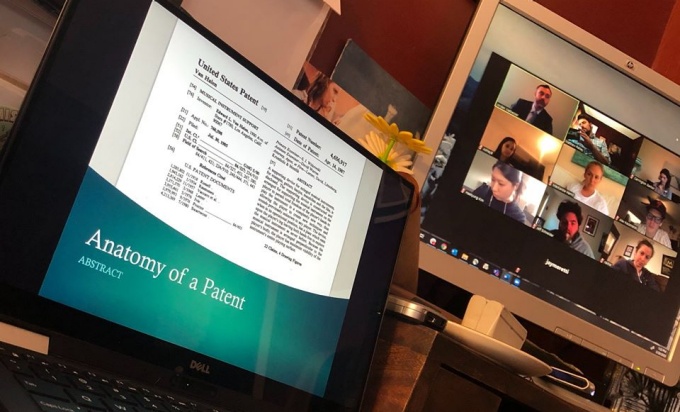

Assistant Clinical Professor Judith Olin meets with students in the Family Violence and Women’s Rights Clinic.

That’s how Professor Kim Diana Connolly approached the School of Law’s transition from in-person instruction to an online learning environment. And with give-and-take and thoughtful improvisation, faculty and students have indeed been making it work.

“The whole clinical program has been working on this since we realized shutdown was a possibility,” says Connolly, who oversees the school’s legal clinics. “Teaching online is not hard. What we’re having to work on is the complicated aspects of doing work by distance with clients.”

For example, some clinic students are able to continue to serve their clients by teleconference. In some instances, clients have experience with signing documents electronically, so that works. But, of course, no one is standing up in court on behalf of clinic clients. Connolly says some clinic students are shifting much of their work to researching and to writing motions — and recognizing that some of the cases they’ve been working on won’t be finished by semester’s end.

Both the clinics and the externship programs have also established virtual office hours so that students in the clinics, as well as those doing externships, will always have faculty and senior staff members available for questions and discussion.

“We’re taking each client and each student attorney situation by situation to make sure they are able to have the best experience possible,” she says. “And the students have been fabulous. They’re absolutely adapting.”

In addition, she says, the students are having an unscripted experience in professional preparedness. “We don’t know how this is going to unfold,” Connolly says. “But this does happen in practice. People may get sick; they may take on other responsibilities. This is actually training students in the skills you need to have a good disaster plan.”

Professor Mark Bartholomew has moved his class in copyright law online. While some of his colleagues are teaching live lessons in cyberspace, he decided that his material could be offered in a series of video-recorded lectures. So early on, he produced the series at the law school, which both made for crisp sound and, he says, “made it feel a little more like it was in the classroom.”

“The pandemic has uprooted some students’ schedules as they move to new living spaces or take care of relatives. So I thought it would be good for the students to have some classes asynchronously, to be able to play my lectures on their own time instead of my time,” he says.

But he recognizes that there are many compromises involved with distance learning. “I think of this as making the best of a bad situation,” Bartholomew says. “It’s not as good as face-to-face learning. You can’t read people’s faces, for one thing.”

The Panopto software he’s using, following an intensive tutorial period, does allow him to do one thing he does in the lecture hall: seamlessly integrate clips from movies, television shows and songs into his lectures. “The raw materials of the cases I teach are about these things,” he says. “And it makes it better than just seeing me on the screen for 90 minutes."

Adjunct Professor Jennifer Scharf ’05 teaches “Representing Medical Professionals and Health Care Facilities.”

For adjunct professor Jennifer Scharf ’05, the coronavirus crisis has become grist for the mill of her course in “Representing Medical Professionals and Health Care Facilities.”

Building on a student suggestion, Scharf has retooled the course around some of the legal questions health care attorneys will address surrounding the response to the pandemic. Students now are creating projects as if they were in-house counsel or an outside counsel to a health care provider, tackling situations that are certain to arise in real life. For example, if an employee is required to report to work but fears carrying the infection back home to an immunocompromised family member, what does employment law say about how she should be treated?

“This is really representative of what they’ll be doing as lawyers,” Scharf says. “What’s important for a health care law attorney is to be able to adapt on the fly, to change what you thought your project of the day was and address the needs of your client. As lawyers, they are going to need to come up with those answers quickly and deliver them to their clients.”

Scharf also oversees the School of Law’s Trial Advocacy Program, including tryouts for the school’s competitive trial teams. “We’re acting on the theory that there will be competitions in the fall,” she says.

And because in-person tryouts for those teams can’t happen this semester, they’re moving that online as well – giving out a fact pattern for a hypothetical case and asking interested students to submit a video of themselves delivering an opening statement for evaluation by the coaches.

Shortly after law schools went to distance learning, the best trial advocacy schools in the country banded together on Zoom conferences to discuss teaching trial advocacy online. “Many of these schools already have exclusively-online courses, so we have been able to build off of their knowledge,” Scharf explains. “Schools that have been our ‘competitors’ in nationwide competitions have become extraordinary allies in designing a meaningful experience for our students.

“Trial Team and Trial Technique are incredibly important courses for our students and for attorneys in the community who hire our students. Just as attorneys are adapting to virtual courtrooms, we are adapting our program, so we can continue to develop top-notch trial lawyers.”